That Moment.

Since Joan Rivers died on September 4, I, like so many people, have mourned the loss of a favorite comedian. I grew up looking forward to her nights as guest host of The Tonight Show, and I’m thankful I had the opportunity to see her live in Las Vegas a few years back, still sharp as ever.

But amidst all the clip reels and montages of her best one-liners, my mind keeps drifting to her daughter, Melissa. Because I know on that Thursday afternoon, in that hospital room in Manhattan, Melissa had experienced That Moment. The moment she looked at her mother’s face and knew, with utter certainty, she was gone forever.

It’s the moment my family had vaguely dreaded from the day my mom was diagnosed. It’s why you cry when you learn the news. You hear “cancer” and the idea of death immediately comes to the forefront, but you have no clear picture of what it looks like. “How do you feel?” you keep asking each day. The question hides an unspoken follow-up: “Do you feel like you’re going to die?”

In the first weeks–days, even–after her diagnosis, every minor ailment took on new significance. Mom woke up with a slight headache. What does that mean? She mentioned her nose is stuffy. Is that bad? She’s having some pain in her knee today. Is that a sign she’s going to die? Even though in retrospect, she would never be healthier than she was at that moment, the specter of her sudden mortality hung over us all.

I remember going shopping with my parents a couple of days after they had shared what was going on. My mom and I were in the shoe section of a department store, and she tried on a pair of suede boots. She liked them, but hesitated at the price tag. I can still hear the bittersweet encouragement in my dad’s voice: “Get the boots.”

Nov. 27, 2010. Two days after I found out about the first scan, five days before confirmed diagnosis.

A couple of weeks later, my mom asked her doctor if she could still take the trip she had planned to visit her best friend in Maryland. “I think you should do what you want,” he told her. She knew he meant it to be reassuring, but she read a deeper meaning into it, too. She repeated this story, and that quote, many times.

When she started her treatment, she had the typical symptoms you hear about–fatigue, nausea–but overall she seemed pretty much the same. She was up cooking, doing laundry, feeding the birds. Her hair didn’t fall out (we were told not everyone’s does) and she still put on full makeup, so she looked the same. On the phone, her voice was as strong and clear as always. And I suddenly had a calming epiphany: She could do this. She could beat it. At the very least, even if the statistics told us she was dying, she wasn’t dying right now.

At my mom’s first treatment, her oncology nurse told her something similar. “Here’s what happening,” she said. “You have a chronic illness, and it’s one we’re going to manage for a long, long time.” Later, when her condition seemed to be improving, my mom reflected on this moment and thanked the nurse. “You didn’t just give me chemo that day,” my mom told her. “You gave me a shot of something else: hope.”

My mom would talk occasionally about the opposite, more grim prospect, usually framed in the context of gratitude. She would weep when she saw the commercials for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “I’m 64. I’ve lived a full life,” she’d say. “These poor kids are only 4 and 5 years old.” She would shake her head at stories in the newspaper about abducted children who had been murdered or people who were killed suddenly in tragic accidents. “They never had a fighting chance. At least I have a fighting chance.”

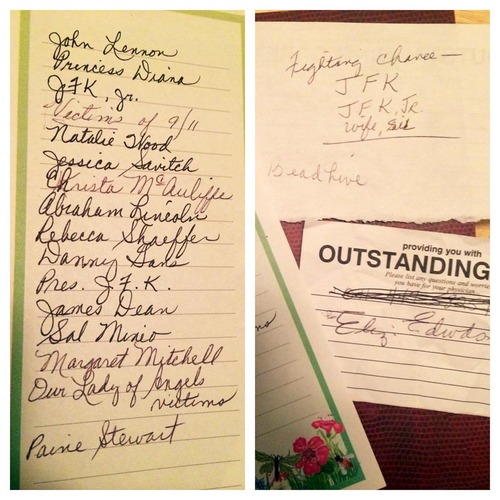

This idea of a fighting chance apparently had been a mantra for her. A couple of weeks ago, when I was home to help sort through some of her things, I found these notes tucked into a journal:

All those poor people. At least she had a fighting chance.

……..

Even in those final weeks, when the reality of her death became imminent, we still held on to that fighting chance. I remember years ago reading a reprint of the obituary Roger Ebert wrote for John Lennon. He commented that when Lennon died, so did the joy of the Beatles era and the possibility it could be recaptured. Even though rationally, everyone knew it wouldn’t have been the same, as long as all four band members were alive, there was still the chance that it could be.

That’s how I felt watching my mom grasp on to those last few days of life. As long as she was still here, still breathing, still smiling at us in recognition after she lost her ability to speak, there was the chance something could be done. The possibility a doctor could suddenly knock on the door with a syringe. “We figured it out! Let me through!” as he made his way to the bed. The opportunity for a miracle.

So when my dad went over that last night to check on her as she slept, then called out for me to come over, I couldn’t believe it had actually happened. She had looked up at him, and he said to her with a smile, “Honey, your eyes are open.” He held her hand, she took one last breath, and he saw the life leave her eyes. When I got to the bed, her eyes were open but unfocused, her mouth drooped to one side. The permanence was violent and immediate. She was gone, forever.

My mind was cleared of all thought. I felt only pure emotion, pure grief. Literally every cell in my brain was focused solely on this moment and its truth. I broke this trance to call my brother, who had just left the house minutes before, to tell him to come back. My dad and I held each other and wept. We recounted the moments before like newscasters trying to make sense of the new details just coming in. Reliving and replaying That Moment, as if we could somehow reverse it.

As I looked into my mother’s eyes–eyes that could no longer look back–I felt disbelief on her behalf. She never imagined this would be her, I thought.

When she had first gone into the hospital a few weeks before, following a mild stroke, we talked to each other on the phone through tears. I asked how she was feeling. “You know, I keep thinking about all the friends with cancer who’ve gone before me, and everything they went through–just to die.”

And now here she was. All of the chemo, the radiation, the wigs, the hats, the scans, the x-rays, the physical therapy, the wheelchairs, the immunity boosters, the diuretics, the potassium pills, the compression socks, the catheters, the painkillers, the greeting cards, the gifts, the soups, the phone calls, the prayers, the tears–all of it got us to this. To her vanishing from herself, betrayed by her own body, a container of lifeless cells on a mattress in our family room.

After the logistical side of death brought us back to reality–a man came into our kitchen and said, “Let me walk you through what’s going to happen. My colleague and I are going to take your mother and very respectfully place her in the velvet-lined bag you see here”–I allowed myself to take one picture, the next morning:

I wanted some record of that last moment. After all, I had photographed so many other moments of my mom’s life, and her death is part of her life. Because the bed was from a hospice program, someone would be coming later that day to pick it up, and I never thought I’d feel sad to say goodbye to a piece of community hospital equipment. I felt significance in the fact that this set-up was so temporary (those chairs are from another room) and would be so easily dismantled, while the events that occurred in that brief window of time would be indelible.

I’ve been promised by friends who’ve gone through similar losses that someday, I’ll have only happy thoughts of my mother. I trust that will be true. For a while, looking at old photos or videos of my mom only took me back to That Moment. But it’s getting better each day. Now I try to channel that grief into the realization that we’re all headed for That Moment ourselves, and rather than being a morbid thought, it’s actually quite liberating. It gives you permission to prioritize, to reject the unnecessary. Other people’s opinions have much less influence, especially when they run counter to your core values and beliefs. You don’t have the time or the patience to tolerate stress. You start to appreciate the small, everyday moments in life–like the time you went with your mom to her weekly bowling league:

For a long time after my mom died, I could hardly get through that video. Now, I celebrate the happy time it captures: when my mom was at her healthiest, surrounded by friends she loved and who loved her, and when the worst thing that happened to her that day was not being able to pick up that split.